Key takeaways

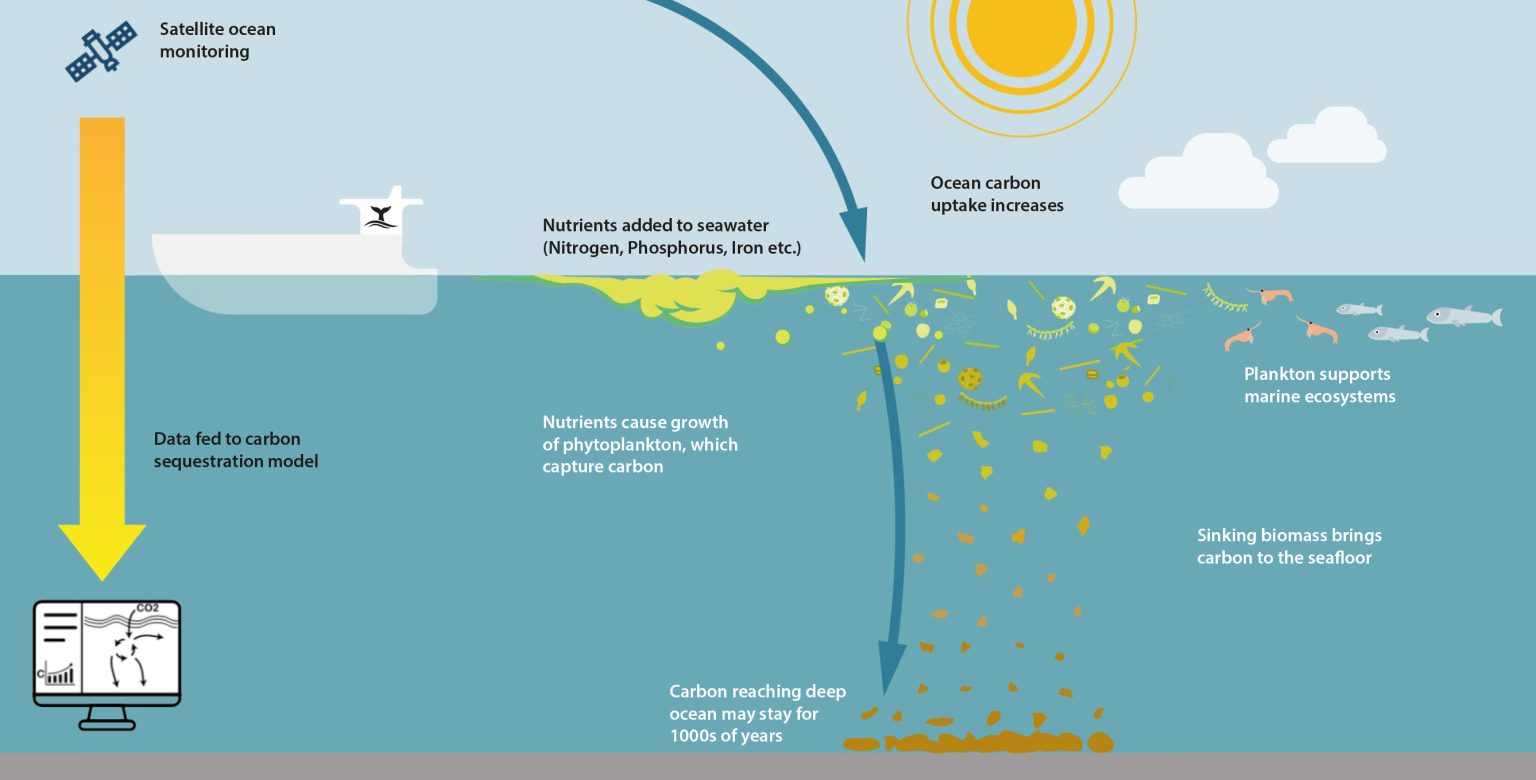

- Adding trace iron in iron-limited waters reliably triggers natural-style blooms; this has been observed at sea, not just in bottles.

- Diatoms (silica-shelled phytoplankton) are pivotal for carbon export; without silicic acid, productivity recycles near the surface.

- Whales likely acted as surface iron recyclers; removing them diminished productivity and altered iron dynamics.

- Natural fertilization hotspots (South Georgia, Patagonian shelf) show fast growth, high standing stocks, and strong export.

- The biggest barriers to new trials are governance and logistics, not basic science: we need larger, longer, permitted field experiments.

From skepticism to sea proof

Dr. Christine Klaas came to iron fertilization wary: “Biology is complicated—surely it isn’t just iron.” Then she sailed. Participating in major Southern Ocean iron experiments (e.g., EisenEx and EIFEX), she saw that a small pulse of iron consistently flipped communities into bloom—with species compositions matching natural events. The crucial difference from lab work: perturbing a real ecosystem.

Why diatoms matter (and why silica does too)

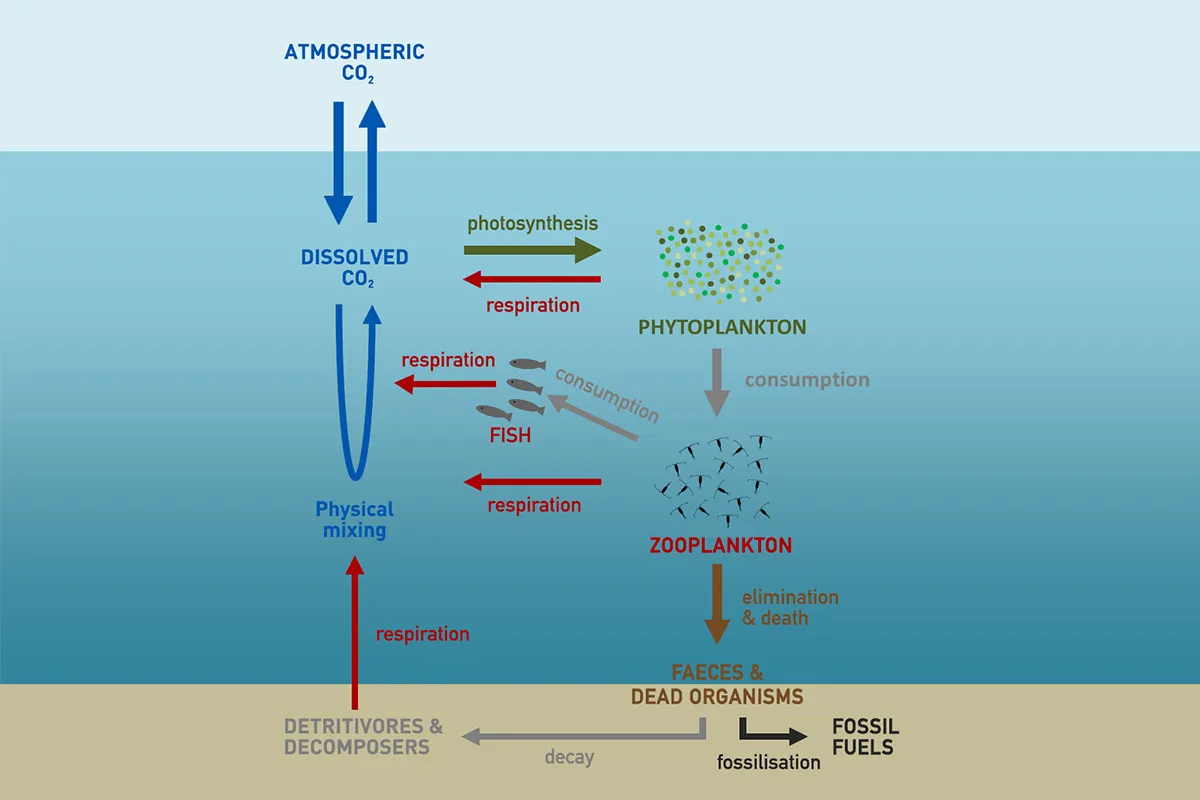

Diatoms require silicic acid to build dense, glasslike frustules. In high-silica regions, many diatoms grow thick, sink fast, and efficiently export carbon to depth. When silica is depleted, non-diatom algae dominate and most of the fixed carbon is recycled in the surface ocean.

Downstream of sub-Antarctic islands like South Georgia, Klaas’ teams find some of the planet’s highest standing stocks—growing roughly once per day even in cold waters—plus strong export signatures, including resting spores captured in sediment traps.

In naturally iron-rich regions, what sinks most efficiently are often resting spores of diatoms—dense, silica-heavy stages that drop rapidly—rather than just senescent cells.

Two “carbon pathways”—not either/or

Some frame a trade-off between (a) carbon that sinks with diatoms and (b) carbon that feeds zooplankton, fish, and higher trophic levels. Klaas rejects this zero-sum view in iron-limited systems:

- Iron, not carbon, is limiting. When iron is available, both primary production and grazing rise.

- Grazers recycle iron at the surface, sustaining productivity; meanwhile, a fraction of biomass still sinks and is exported.

- Both can happen at once: food webs thrive while a measurable fraction of biomass still sinks; export efficiency hinges on diatoms and silica.

Whales as iron recyclers

Whales feed and defecate near the surface. Their liquid feces likely kept iron in the euphotic zone, supporting diatoms, krill, and predators. Industrial whaling removed much of that surface recycling engine; notably, Southern Ocean blue whales remain far below historical levels despite decades without whaling—consistent with altered surface iron dynamics and reduced productivity.

By feeding at depth and defecating near the surface, whales effectively helped retain iron in the euphotic zone—acting as ecosystem engineers that sustained diatom productivity.

Natural laboratories: islands, shelves, and dust

- South Georgia & sub-Antarctic islands: Continuous natural iron inputs (glacial melt, shelf sediments) sustain huge blooms and measurable export.

- Kerguelen Plateau: A classic natural “iron world” where island and shelf inputs drive large, recurrent blooms.

- Patagonian shelf: A vast, naturally fertilized region with rich fisheries—an under-studied model for iron-driven productivity.

- Dust & fires: Episodic iron pulses (e.g., Australian wildfires) demonstrate basin-scale biological responses.

What the experiments showed (and didn’t)

Showed

- Trace iron reliably sparks blooms with community structures mirroring natural events.

- Export can be strong (e.g., mass sinking events; resting spore fluxes in traps).

- No field evidence that fertilized blooms generate net GHG increases that outweigh CO₂ uptake in these HNLC settings.

Didn’t (yet) quantify enough

- Permanence and the exported fraction over seasonal–annual scales.

- Outcomes across iron regimes (pulses vs. continuous) and silica landscapes.

- Downstream nutrient redistribution (“nutrient robbing”) under different siting strategies.

Governance: the London Convention/Protocol problem

Klaas emphasizes that LC/LP permits scientific trials, but the process is onerous. Long pre- and post-monitoring requirements, combined with scarce polar ship time, make projects logistically near-impossible for single nations. International programs—with shared platforms, planning, and verification—could solve the bottleneck.

A coordinated, multi-nation program with shared vessels and pre-agreed monitoring windows could satisfy LC/LP requirements without making ship time the rate-limiting step.

Justice, islands, and what OIF can (and can’t) do

Small Pacific Island States may have the strongest livelihood incentives (fisheries) and legal latitude (within EEZs) to test whether iron limitation suppresses local productivity. For global carbon removal, Klaas is clear: the Southern Ocean is the only venue large and nutrient-rich enough to matter.

OIF is not a substitute for emissions mitigation. At best, optimized programs might remove on the order of ~10% of current annual CO₂ emissions—while the world cuts to near-zero.

Myths, rebutted

- “Blooms will emit more potent GHGs than they remove.” Field data and vast natural bloom regions argue otherwise.

- “It’s either fish or carbon export.” In iron-limited systems, iron raises both production and food-web throughput; a fraction still exports.

- “Chemistry solutions are safer than biology.” Both alter ocean processes; both need evidence, monitoring, and rules. Neither gets a free pass.

What good science needs next

- Bigger, longer, permitted experiments in the right places (iron-limited, silica-replete; strategic relative to fronts/gyres).

- End-to-end MRV: physiology, community dynamics, silica/iron cycling, export (traps, radionuclides), and downstream biogeochemistry.

- Coupled models tuned with new field data to resolve nutrient redistribution and net carbon benefit.

- Governance fit for purpose: predictable permitting, shared ships, transparent oversight, and equitable benefit-sharing—especially for regions bearing climate risk.

The reframing: restoration, not “dumping”

Think in terms of Ocean Iron Restoration: reviving dampened surface-iron recycling (once aided by whales) so existing nutrients can be used.

Klaas’ view aligns with a powerful narrative: we removed surface-iron recyclers (whales) and curtailed natural fertilization. Ocean Iron Restoration aims to restart a dampened process with trace iron (C:Fe ratios of tens of thousands to one), letting the ocean use nutrients it already holds.

A cinematic call to curiosity

Natural iron worlds—South Georgia’s emerald plumes, the Patagonian shelf’s teeming life—show what’s possible. Filming, measuring, and explaining these places could reset public intuition: this is what iron does; this is what the ocean looks like with and without it.

Closing

Dr. Christine Klaas isn’t pitching shortcuts. She’s asking for serious science at sea—the kind that can answer the remaining questions and guide policy with confidence. The switch is known. The ocean is waiting. Now we need the permits, ships, and courage to flip it—carefully, transparently, and for the common good.

The choice isn’t between perfection and inaction—it’s between measured learning at sea and leaving a known lever untouched.

FAQ

Who is Dr. Christine Klaas?

Dr. Christine Klaas is a senior scientist at the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) and a plankton ecologist with field experience from major Southern Ocean iron fertilization experiments (e.g., EisenEx, EIFEX).

What is this page about?

This page summarizes a recorded conversation with Dr. Klaas covering iron limitation, diatoms and silica, whales as surface iron recyclers, natural fertilization hotspots, governance under the London Convention/Protocol, and priorities for future field science.