Introduction

Recorded on South Africa’s coast, marine ecologist Dr. Matthew Savoca explores whales, krill, iron, and the changing Southern Ocean. We examine how whale populations shape marine productivity, why krill matter far beyond Antarctica, and whether carefully designed iron restoration could help repair disrupted ocean cycles.

From Seabirds to Whales

Dr. Matthew Savoca grew up in New York City, captivated by wildlife. He began with seabird ecology—birds that forage across vast seas and return to land, letting researchers sample the ocean’s condition. That lens widened to whales, which face similar challenges: finding food across shifting seascapes while coping with climate change, pollution, and fisheries interactions.

Climate Change: It’s the Rate of Change

For large predators, the story isn’t just how warm the ocean is—it’s how fast conditions shift. Whales tolerate big temperature ranges, but their prey often can’t track rapid changes. Small, persistent increases in foraging effort can cascade into lower reproduction and slower population growth.

Recent decades show a sharp, volatile climate signal. Prey like krill shift or contract ranges, sometimes forcing whales to travel farther for fewer returns.

Antarctic Krill: Tiny, Pivotal

By “krill” we mainly mean Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba)—a single species with biomass in the hundreds of millions of tons, among the most abundant wild animals on Earth. Krill link phytoplankton to top predators (penguins, seals, whales) and power the Southern Ocean food web.

Krill are flexible feeders: they graze on diatoms when blooms are present, consume other zooplankton and detritus (“marine snow”), and can feed throughout the water column—even near the seafloor in winter. Climate change, sea-ice loss, and active krill fisheries are compressing habitat and stressing populations.

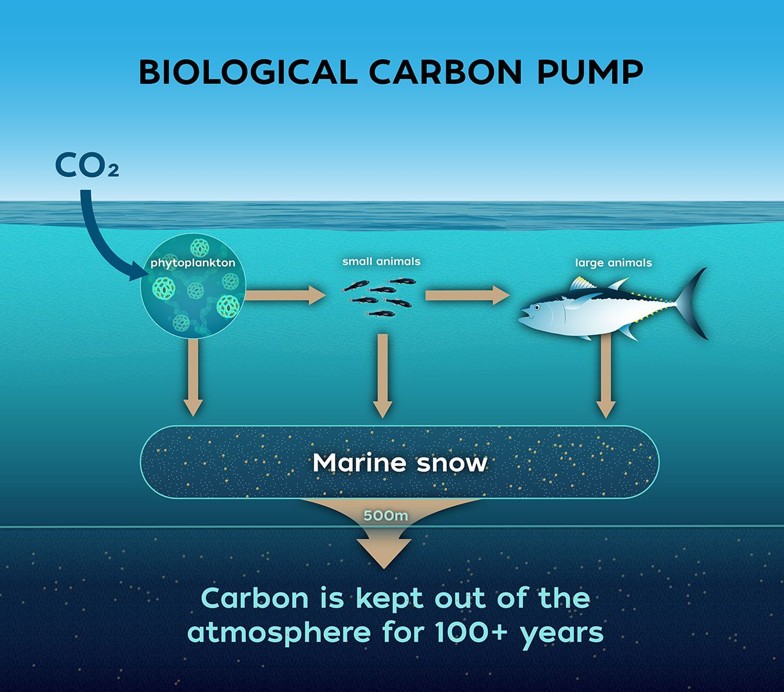

The Biological Carbon Pump

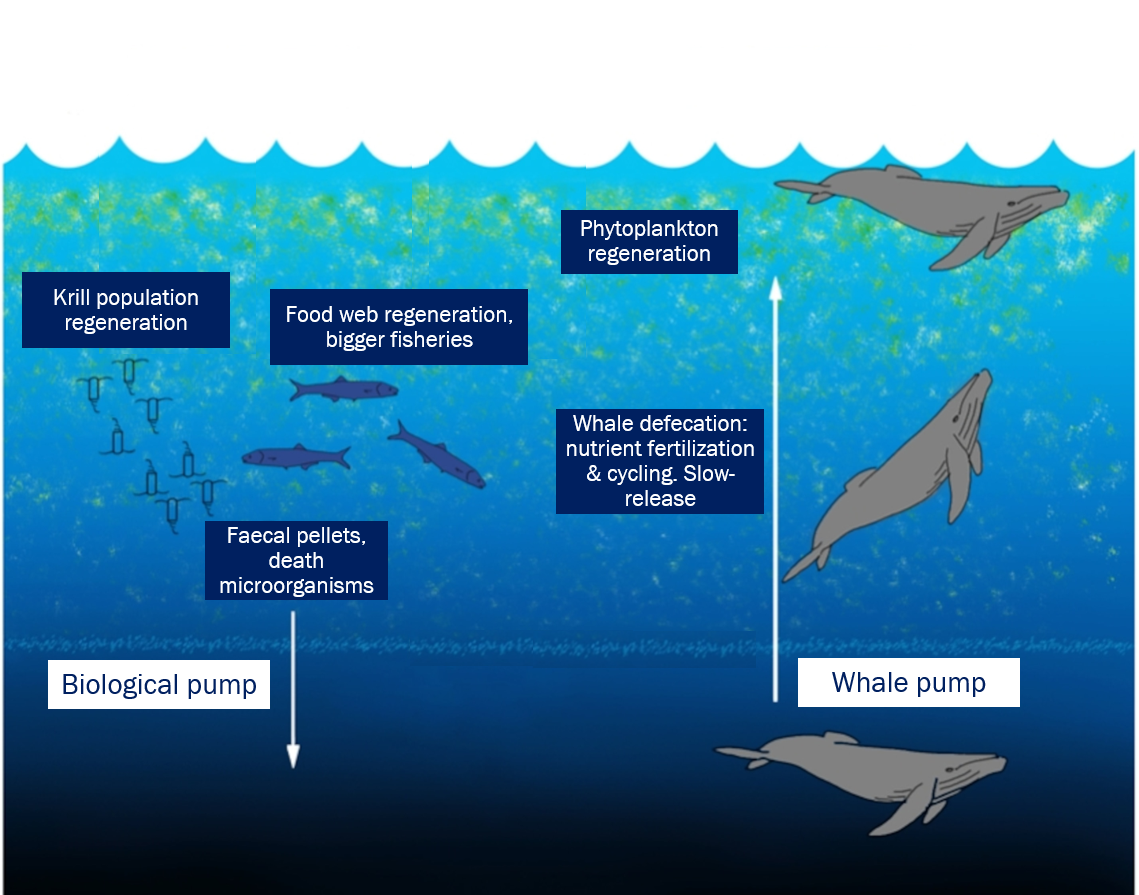

Phytoplankton fix CO₂. Krill eat phytoplankton; their fecal pellets and molts sink, shuttling carbon to depth. Over time, this living “pump” stores carbon away from the atmosphere—from years to millennia—via growth, grazing, sinking, and decomposition.

- Direct biomass: Carbon in krill bodies that sinks after death.

- Accelerated export: Dense pellets and molts are efficient vehicles for carbon to leave surface waters.

Whales as Iron Recyclers

Whales consume iron-rich krill but need only trace iron themselves. The excess is released in feces that fertilizes surface waters. Microbes from whale guts bind to iron and make it more bioavailable to diatoms—boosting local productivity.

Southern Ocean blue whales were reduced by >99% within ~70 years. Beyond the ecological loss, whaling removed a key nutrient-recycling service. Blue whales have recovered only to a few percent of historic levels, unlike some other baleen whales.

Iron Addition Experiments: What We Know

Past iron-fertilization campaigns consistently showed that trace iron additions in iron-limited waters trigger phytoplankton blooms. Yet they rarely measured responses above phytoplankton. One notable exception observed copepod growth within the fertilized patch—hinting that higher-trophic responses can be rapid. Overall, evidence for zooplankton and larger animals remains thin.

Restoration, Not Geoengineering?

Extractive activities already “engineered” the ocean by stripping biomass and nutrient recyclers. If science shows that bounded, careful iron additions restore diatoms and krill—without harmful side effects—this can be framed as ecological restoration, not reckless manipulation.

- Stepwise scaling: small → medium → larger trials only if results warrant.

- Clear objectives: measure krill growth/reproduction, not just chlorophyll.

- Independent MRV: ecosystem health, export flux, unintended impacts.

- Adaptive stops: halt or reverse if adverse signals appear.

Where (and Why) to Test

Southern Ocean: High potential for ecosystem restoration (krill, whales). Carbon may be recycled strongly at the surface as food webs respond; sequestration benefits may accrue over longer horizons via a strengthened biological pump.

Equatorial Pacific & Oligotrophic Seas: Potentially more efficient carbon sequestration in the near term because there’s less grazing—more bloom material can sink. Restoration of specific food webs may be less immediate. Objectives and safeguards should differ from Southern Ocean trials.

The Carbon Permanence Puzzle

Permanence depends on pathways: rapid surface remineralization vs. deep export (pellets, molts, carcasses) that can store carbon for decades to millennia. Most large-scale models simplify or omit biology, yet permanence hinges on who eats what, where, and when. Honest accounting means uncertainty bands, improved mechanistic models, and funding experiments that measure biological fluxes—not just chlorophyll.

Science, Capital & Guardrails

Commercialization without strong rules risks harm, but capital also accelerates solutions. A pragmatic path mirrors careful clinical programs:

- Pilot: demonstrate effects on zooplankton/krill; verify no harm.

- Scale cautiously: replicate across sites; strengthen monitoring.

- Codify guardrails: permits, independent oversight, transparent data.

- Align incentives: finance tied to verified ecological outcomes.

Closing Thoughts

The ocean’s biggest stories hinge on its smallest actors. Krill concentrate iron and move carbon; whales fertilize diatoms and organize productivity; microbes make nutrients usable. After a century of subtracting, it may be time to test what giving back looks like—carefully, transparently, and guided by data.

FAQ

Who is Dr. Matthew Savoca?

Dr. Matthew Savoca is a marine ecologist known for research on whale ecology, nutrient cycling (including iron recycling by whales), and the Southern Ocean food web.

What is this page about?

This page summarizes a recorded conversation with Dr. Matthew Savoca covering whales, Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba), iron availability, and the biological carbon pump, with discussion of careful iron restoration as an ecosystem repair strategy.