The “Fish Kills” Misconception

.jpg)

One of the most emotionally charged misconceptions surrounding Ocean Iron Fertilization (OIF) is the fear that it could lead to massive fish kills—that stimulating phytoplankton blooms will deplete oxygen, create toxic conditions, or collapse marine food webs. These concerns arise because the public associates all “algal blooms” with coastal disasters: dead fish washing ashore, foul odors, and suffocating waters. However, these events are products of eutrophication in enclosed, polluted coastal systems, not of trace-nutrient restoration in the open ocean. In fact, every scientific OIF experiment to date has shown the opposite effect: short-term stimulation of plankton growth, increased zooplankton abundance, and stronger food-web productivity—without any recorded fish mortality.

Understanding Where Fish Kills Actually Happen

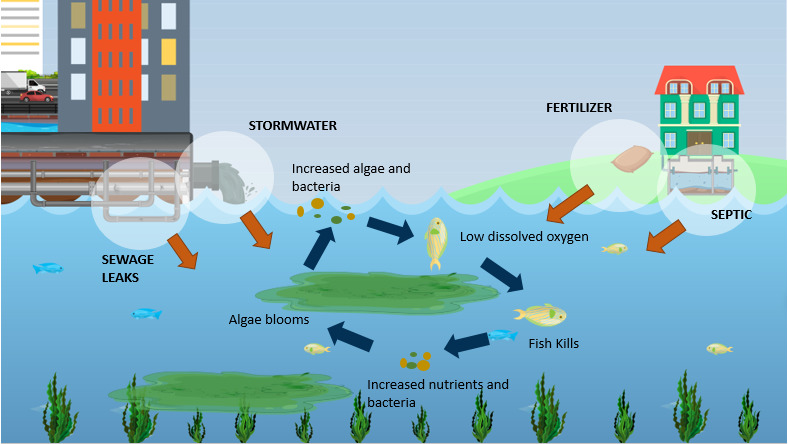

Fish kills are typically a symptom of nutrient overload and poor circulation. In rivers, estuaries, and semi-enclosed seas (like the Gulf of Mexico, Baltic Sea, and Bay of Bengal), runoff from agriculture and sewage adds large quantities of nitrogen and phosphorus. These macronutrients drive uncontrolled algal growth. When the algae die and decay, bacteria consume oxygen faster than it can be replenished, leading to hypoxia or anoxia. Fish, unable to escape the low-oxygen zones, suffocate.

In contrast, the Southern Ocean, equatorial Pacific, and subarctic Pacific—the regions targeted for OIF—are open, wind-mixed systems with high oxygen exchange and low background productivity due to chronic iron limitation. These waters are not nutrient-saturated; they are nutrient-idle—rich in nitrate and phosphate but biologically underused. Adding minute quantities of iron allows the ecosystem to use what’s already there, not to overload it.

The Iron Additions Are Minuscule and Safe

An OIF event involves releasing iron as a very diluted liquid solution, usually ferrous sulfate (FeSO₄) in seawater. Even directly within the fertilized patch, iron concentrations rise only to about 0.000056–0.000112 mg/L—

2,500–5,000 times lower than the WHO drinking-water guideline (0.3 mg/L), and

2,000–3,700 times lower than the marine ecological sensitivity threshold (~0.21 mg/L).

These values demonstrate that OIF operates thousands of times below any toxicity or ecological stress limit. There is no mechanism by which such trace additions could poison fish or planktonic food chains. The iron is immediately diluted, oxidized, complexed, and recycled within the ocean’s natural chemistry.

Oxygen Does Not Deplete in OIF—It Is Recycled

The “oxygen depletion” argument for fish kills assumes that large amounts of decomposing biomass consume oxygen faster than it can be replenished. This is true in stagnant, stratified water bodies—but not in the Southern Ocean. Here, intense wind-driven mixing, storms, and wave turbulence continually ventilate surface waters.

Moreover, OIF stimulates diatom blooms, which sink rapidly after growth. This export removes organic matter from the upper layer before it can decay locally, preventing oxygen drawdown at the surface. Observations from IronEx II, SOFeX, SEEDS, SERIES, and LOHAFEX show no measurable oxygen decline following iron addition—only short-lived productivity peaks and rapid ecosystem re-equilibration.

In fact, by stimulating photosynthesis, OIF initially increases oxygen production in the mixed layer. Phytoplankton release oxygen during daylight growth, offsetting any later decomposition effects.

No Evidence of Fish or Zooplankton Mortality in Any OIF Experiment

Over 13 major international OIF field campaigns have been conducted since 1993 across the equatorial Pacific, Southern Ocean, subarctic Pacific, and North Atlantic. Each experiment deployed a fertilized patch (ranging from 50–300 km²), tracked it for several weeks, and measured chemical, biological, and ecological responses. The results were remarkably consistent:

No fish kills or zooplankton die-offs were observed.

No toxic algae outbreaks were recorded.

No oxygen depletion events occurred within or downstream of the fertilized area.

Enhanced grazing by zooplankton and increased particulate carbon flux were documented, showing that the ecosystem responded by growing—not collapsing.

These data conclusively separate OIF from coastal eutrophication dynamics. The ocean simply does not behave like a lake or river delta.

Why the “Fish Kill” Image Persists

The fear of fish kills stems from misapplied analogies. People associate “adding nutrients” with the coastal red tides that devastate fisheries. Yet OIF targets the opposite end of the productivity spectrum—iron-poor, oxygen-rich, open-ocean waters.

In the Gulf of Mexico, for example, fish kills occur because agricultural fertilizers feed massive blooms of cyanobacteria and dinoflagellates. When these organisms die, their decomposition consumes oxygen in bottom waters already isolated by the low-density freshwater layer from the Mississippi River. The Southern Ocean has no such stagnant layer—it is a global engine of deep-water formation where oxygen is continuously replenished.

Confusing OIF with agricultural runoff is like confusing a raindrop with a flood.

Ecosystem Restoration, Not Degradation

Iron addition does not harm marine life—it helps restore the biological pump that nourishes fish populations. Historically, vast oceanic ecosystems were fertilized naturally by whale feces, krill swarms, and dust storms. Industrial whaling, overfishing, and reduced atmospheric dust inputs have disrupted this nutrient cycling. By restoring trace iron, OIF revives the base of the marine food web: diatoms grow, zooplankton thrive, and fish larvae gain more food.

In the LOHAFEX experiment (South Atlantic, 2009), scientists observed a rapid increase in copepods and microzooplankton that fed on the bloom, showing an upward trophic benefit—not harm. The iron enhancement supported life rather than destroying it.

Why Toxic Blooms Are Impossible Under OIF Conditions

Toxic or harmful algal blooms (HABs) typically consist of dinoflagellates or cyanobacteria that require calm, stratified, nutrient-rich conditions near coasts. These taxa are virtually absent in the cold, turbulent, iron-limited Southern Ocean. The phytoplankton that dominate OIF responses—diatoms—are non-toxic and essential to marine food webs. They form silica shells that sink upon death, driving carbon sequestration while feeding krill, copepods, and fish larvae.

Furthermore, OIF additions occur under strict monitoring: water samples are analyzed for species composition, toxins, and physiological stress indicators. Across all experiments, no harmful or toxic phytoplankton species proliferated after iron enrichment. The biological succession mirrored natural dust-driven bloom events.

Biological Safeguards in OIF Implementation

OIF operations are designed with multiple safety layers:

Extremely low iron concentrations (thousands of times below any risk threshold).

Use of liquid-diluted ferrous sulfate, ensuring rapid dispersion and no aggregation.

Targeting HNLC zones far offshore, avoiding shallow habitats and coastal fisheries.

Continuous monitoring of oxygen, pH, plankton, and trace metals.

Adaptive management, with immediate termination criteria if anomalies occur.

These protocols make OIF among the most controlled marine interventions ever attempted. The notion that it could cause fish kills ignores both ocean physics and modern oversight standards.

Lessons from Nature: Iron Stimulates Life, Not Death

Natural iron enrichment events—from volcanic ash clouds to Saharan dust plumes—have been repeatedly observed to trigger phytoplankton blooms that increase fish stocks, not kill them. After the 2008 eruption of Mount Kasatochi (Aleutians), a natural iron pulse fertilized the North Pacific and was followed by a record sockeye salmon run in 2010—the largest in 50 years. Nature’s own “OIF experiments” consistently support life and enhance fisheries.

Human-managed OIF simply mirrors these processes at micro-scale precision, ensuring safety while reviving natural productivity.

Conclusion

The “fish kills” narrative surrounding OIF is a myth born from coastal analogies and a misunderstanding of ocean ecology. Fish kills occur in stagnant, over-fertilized, nearshore waters—not in the vast, ventilated, iron-starved high seas. The trace, liquid-diluted iron added during OIF is thousands of times below toxic limits, rapidly dispersed, and absorbed into the natural nutrient cycle. Far from harming marine life, OIF revives the base of the food web, restores balance to iron-depleted ecosystems, and may help rebuild fish populations weakened by historical disruptions.

In the open ocean, iron means life—not death.

← Back to all misconceptions